This post is the second in the series ECC: a gentle introduction.

In the previous post, we have seen how elliptic curves over the real numbers can be used to define a group. Specifically, we have defined a rule for point addition: given three aligned points, their sum is zero ($P + Q + R = 0$). We have derived a geometric method and an algebraic method for computing point additions.

We then introduced scalar multiplication ($nP = P + P + \cdots + P$) and we found out an “easy” algorithm for computing scalar multiplication: double and add.

Now we will restrict our elliptic curves to finite fields, rather than the set of real numbers, and see how things change.

The field of integers modulo p

A finite field is, first of all, a set with a finite number of elements. An example of finite field is the set of integers modulo $p$, where $p$ is a prime number. It is generally denoted as $\mathbb{Z}/p$, $GF(p)$ or $\mathbb{F}_p$. We will use the latter notation.

In fields we have two binary operations: addition (+) and multiplication (·). Both are closed, associative and commutative. For both operations, there exist a unique identity element, and for every element there’s a unique inverse element. Finally, multiplication is distributive over the addition: $x \cdot (y + z) = x \cdot y + x \cdot z$.

The set of integers modulo $p$ consists of all the integers from 0 to $p - 1$. Addition and multiplication work as in modular arithmetic (also known as “clock arithmetic”). Here are a few examples of operations in $\mathbb{F}_{23}$:

- Addition: $(18 + 9) \bmod{23} = 4$

- Subtraction: $(7 - 14) \bmod{23} = 16$

- Multiplication: $4 \cdot 7 \bmod{23} = 5$

-

Additive inverse: $-5 \bmod{23} = 18$

Indeed: $(5 + (-5)) \bmod{23} = (5 + 18) \bmod{23} = 0$

-

Multiplicative inverse: $9^{-1} \bmod{23} = 18$

Indeed: $9 \cdot 9^{-1} \bmod{23} = 9 \cdot 18 \bmod{23} = 1$

If these equations don’t look familiar to you and you need a primer on modular arithmetic, check out Khan Academy.

As we already said, the integers modulo $p$ are a field, and therefore all the properties listed above hold. Note that the requirement for $p$ to be prime is important! The set of integers modulo 4 is not a field: 2 has no multiplicative inverse (i.e. the equation $2 \cdot x \bmod{4} = 1$ has no solutions).

Division modulo p

We will soon define elliptic curves over $\mathbb{F}_p$, but before doing so we need a clear idea of what $x / y$ means in $\mathbb{F}_p$. Simply put: $x / y = x \cdot y^{-1}$, or, in plain words, $x$ over $y$ is equal to $x$ times the multiplicative inverse of $y$. This fact is not surprising, but gives us a basic method to perform division: find the multiplicative inverse of a number and then perform a single multiplication.

Computing the multiplicative inverse can be “easily” done with the extended Euclidean algorithm, which is $O(\log p)$ (or $O(k)$ if we consider the bit length) in the worst case.

We won’t enter the details of the extended Euclidean algorithm, as it is off-topic, however here’s a working Python implementation:

def extended_euclidean_algorithm(a, b):

"""

Returns a three-tuple (gcd, x, y) such that

a * x + b * y == gcd, where gcd is the greatest

common divisor of a and b.

This function implements the extended Euclidean

algorithm and runs in O(log b) in the worst case.

"""

s, old_s = 0, 1

t, old_t = 1, 0

r, old_r = b, a

while r != 0:

quotient = old_r // r

old_r, r = r, old_r - quotient * r

old_s, s = s, old_s - quotient * s

old_t, t = t, old_t - quotient * t

return old_r, old_s, old_t

def inverse_of(n, p):

"""

Returns the multiplicative inverse of

n modulo p.

This function returns an integer m such that

(n * m) % p == 1.

"""

gcd, x, y = extended_euclidean_algorithm(n, p)

assert (n * x + p * y) % p == gcd

if gcd != 1:

# Either n is 0, or p is not a prime number.

raise ValueError(

'{} has no multiplicative inverse '

'modulo {}'.format(n, p))

else:

return x % p

Elliptic curves in $\mathbb{F}_p$

Now we have all the necessary elements to restrict elliptic curves over $\mathbb{F}_p$. The set of points, that in the previous post was: $$\begin{array}{rcl} \left\{(x, y) \in \mathbb{R}^2 \right. & \left. | \right. & \left. y^2 = x^3 + ax + b, \right. \\ & & \left. 4a^3 + 27b^2 \ne 0\right\}\ \cup\ \left\{0\right\} \end{array}$$ now becomes: $$\begin{array}{rcl} \left\{(x, y) \in (\mathbb{F}_p)^2 \right. & \left. | \right. & \left. y^2 \equiv x^3 + ax + b \pmod{p}, \right. \\ & & \left. 4a^3 + 27b^2 \not\equiv 0 \pmod{p}\right\}\ \cup\ \left\{0\right\} \end{array}$$

where 0 is still the point at infinity, and $a$ and $b$ are two integers in $\mathbb{F}_p$.

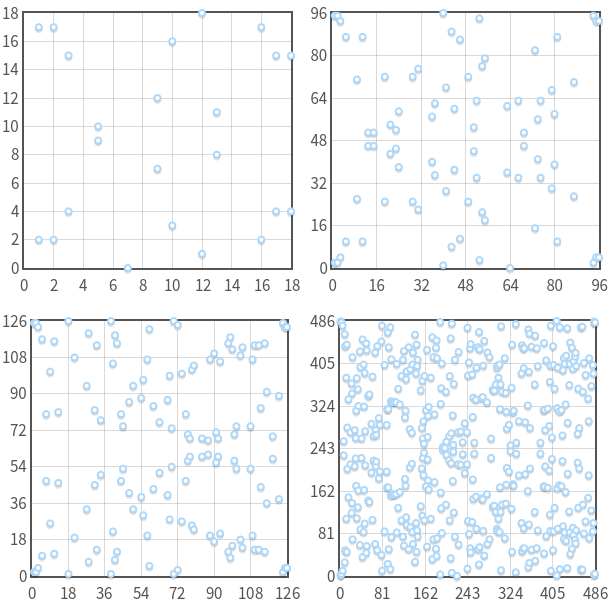

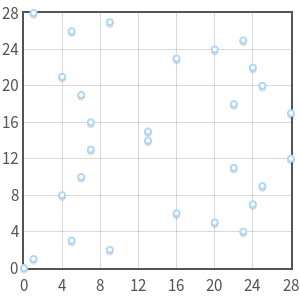

What previously was a continuous curve is now a set of disjoint points in the $xy$-plane. But we can prove that, even if we have restricted our domain, elliptic curves in $\mathbb{F}_p$ still form an abelian group.

Point addition

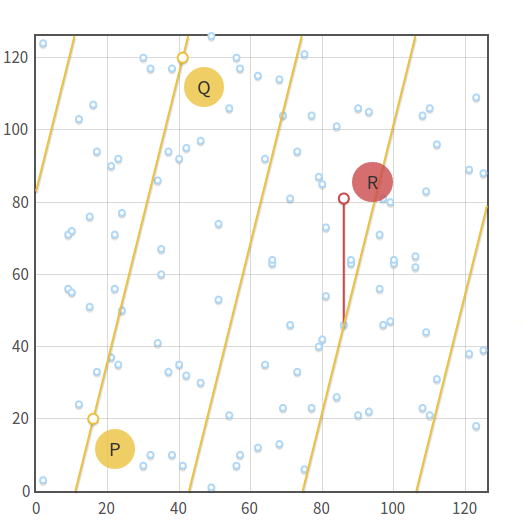

Clearly, we need to change a bit our definition of addition in order to make it work in $\mathbb{F}_p$. With reals, we said that the sum of three aligned points was zero ($P + Q + R = 0$). We can keep this definition, but what does it mean for three points to be aligned in $\mathbb{F}_p$?

We can say that three points are aligned if there’s a line that connects all of them. Now, of course, lines in $\mathbb{F}_p$ are not the same as lines in $\mathbb{R}$. We can say, informally, that a line in $\mathbb{F}_p$ is the set of points $(x, y)$ that satisfy the equation $ax + by + c \equiv 0 \pmod{p}$ (this is the standard line equation, with the addition of “$(\text{mod}\ p)$”).

Given that we are in a group, point addition retains the properties we already know:

- $Q + 0 = 0 + Q = Q$ (from the definition of identity element).

- Given a non-zero point $Q$, the inverse $-Q$ is the point having the same abscissa but opposite ordinate. Or, if you prefer, $-Q = (x_Q, -y_Q \bmod{p})$. For example, if a curve in $\mathbb{F}_{29}$ has a point $Q = (2, 5)$, the inverse is $-Q = (2, -5 \bmod{29}) = (2, 24)$.

- Also, $P + (-P) = 0$ (from the definition of inverse element).

Algebraic sum

The equations for calculating point additions are exactly the same as in the previous post, except for the fact that we need to add “$\text{mod}\ p$” at the end of every expression. Therefore, given $P = (x_P, y_P)$, $Q = (x_Q, y_Q)$ and $R = (x_R, y_R)$, we can calculate $P + Q = -R$ as follows: $$\begin{align*} x_R & = (m^2 - x_P - x_Q) \bmod{p} \\ y_R & = [y_P + m(x_R - x_P)] \bmod{p} \\ & = [y_Q + m(x_R - x_Q)] \bmod{p} \end{align*}$$

If $P \ne Q$, the the slope $m$ assumes the form: $$m = (y_P - y_Q)(x_P - x_Q)^{-1} \bmod{p}$$

Else, if $P = Q$, we have: $$m = (3 x_P^2 + a)(2 y_P)^{-1} \bmod{p}$$

It’s not a coincidence that the equations have not changed: in fact, these equations work in every field, finite or infinite (with the exception of $\mathbb{F}_2$ and $\mathbb{F}_3$, which are special cased). Now I feel I have to provide a justification for this fact. The problem is: proofs for the group law generally involve complex mathematical concepts. However, I found a proof from Stefan Friedl that uses only elementary concepts. Read it if you are interested in why these equations work in (almost) every field.

Back to us — we won’t define a geometric method: in fact, there are a few problems with that. For example, in the previous post, we said that to compute $P + P$ we needed to take the tangent to the curve in $P$. But without continuity, the word “tangent” does not make any sense. We can workaround this and other problems, however a pure geometric method would just be too complicated and not practical at all.

Instead, you can play with the interactive tool I’ve written for computing point additions.

The order of an elliptic curve group

We said that an elliptic curve defined over a finite field has a finite number of points. An important question that we need to answer is: how many points are there exactly?

Firstly, let’s say that the number of points in a group is called the order of the group.

Trying all the possible values for $x$ from 0 to $p - 1$ is not a feasible way to count the points, as it would require $O(p)$ steps, and this is “hard” if $p$ is a large prime.

Luckily, there’s a faster algorithm for computing the order: Schoof’s algorithm. I won’t enter the details of the algorithm — what matters is that it runs in polynomial time, and this is what we need.

Scalar multiplication and cyclic subgroups

As with reals, multiplication can be defined as: $$n P = \underbrace{P + P + \cdots + P}_{n\ \text{times}}$$

And, again, we can use the double and add algorithm to perform multiplication in $O(\log n)$ steps (or $O(k)$, where $k$ is the number of bits of $n$). I’ve written an interactive tool for scalar multiplication too.

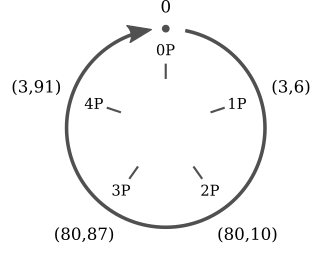

Multiplication over points for elliptic curves in $\mathbb{F}_p$ has an interesting property. Take the curve $y^2 \equiv x^3 + 2x + 3 \pmod{97}$ and the point $P = (3, 6)$. Now calculate all the multiples of $P$:

- $0P = 0$

- $1P = (3, 6)$

- $2P = (80, 10)$

- $3P = (80, 87)$

- $4P = (3, 91)$

- $5P = 0$

- $6P = (3, 6)$

- $7P = (80, 10)$

- $8P = (80, 87)$

- $9P = (3, 91)$

- …

Here we can immediately spot two things: firstly, the multiples of $P$ are just five: the other points of the elliptic curve never appear. Secondly, they are repeating cyclically. We can write:

- $5kP = 0$

- $(5k + 1)P = P$

- $(5k + 2)P = 2P$

- $(5k + 3)P = 3P$

- $(5k + 4)P = 4P$

for every integer $k$. Note that these five equations can be “compressed” into a single one, thanks to the modulo operator: $kP = (k \bmod{5})P$.

Not only that, but we can immediately verify that these five points are closed under addition. Which means: however I add $0$, $P$, $2P$, $3P$ or $4P$, the result is always one of these five points. Again, the other points of the elliptic curve never appear in the results.

The same holds for every point, not just for $P = (3, 6)$. In fact, if we take a generic $P$: $$nP + mP = \underbrace{P + \cdots + P}_{n\ \text{times}} + \underbrace{P + \cdots + P}_{m\ \text{times}} = (n + m)P$$

Which means: if we add two multiples of $P$, we obtain a multiple of $P$ (i.e. multiples of $P$ are closed under addition). This is enough to prove that the set of the multiples of $P$ is a cyclic subgroup of the group formed by the elliptic curve.

A “subgroup” is a group which is a subset of another group. A “cyclic subgroup” is a subgroup which elements are repeating cyclically, like we have shown in the previous example. The point $P$ is called generator or base point of the cyclic subgroup.

Cyclic subgroups are the foundations of ECC and other cryptosystems. We will see why in the next post.

Subgroup order

We can ask ourselves what the order of a subgroup generated by a point $P$ is (or, equivalently, what the order of $P$ is). To answer this question we can’t use Schoof’s algorithm, because that algorithm only works on whole elliptic curves, not on subgroups. Before approaching the problem, we need a few more bits:

- So far, we have the defined the order as the number of points of a group. This definition is still valid, but within a cyclic subgroup we can give a new, equivalent definition: the order of $P$ is the smallest positive integer $n$ such that $nP = 0$. In fact, if you look at the previous example, our subgroup contained five points, and we had $5P = 0$.

- The order of $P$ is linked to the order of the elliptic curve by Lagrange’s theorem, which states that the order of a subgroup is a divisor of the order of the parent group. In other words, if an elliptic curve contains $N$ points and one of its subgroups contains $n$ points, then $n$ is a divisor of $N$.

These two information together give us a way to find out the order of a subgroup with base point $P$:

- Calculate the elliptic curve’s order $N$ using Schoof’s algorithm.

- Find out all the divisors of $N$.

- For every divisor $n$ of $N$, compute $nP$.

- The smallest $n$ such that $nP = 0$ is the order of the subgroup.

For example, the curve $y^2 = x^3 - x + 3$ over the field $\mathbb{F}_{37}$ has order $N = 42$. Its subgroups may have order $n = 1$, $2$, $3$, $6$, $7$, $14$, $21$ or $42$. If we try $P = (2, 3)$ we can see that $P \ne 0$, $2P \ne 0$, …, $7P = 0$, hence the order of $P$ is $n = 7$.

Note that it’s important to take the smallest divisor, not a random one. If we proceeded randomly, we could have taken $n = 14$, which is not the order of the subgroup, but one of its multiples.

Another example: the elliptic curve defined by the equation $y^2 = x^3 - x + 1$ over the field $\mathbb{F}_{29}$ has order $N = 37$, which is a prime. Its subgroups may only have order $n = 1$ or $37$. As you can easily guess, when $n = 1$, the subgroup contains only the point at infinity; when $n = N$, the subgroup contains all the points of the elliptic curve.

Finding a base point

For our ECC algorithms, we want subgroups with a high order. So in general we will choose an elliptic curve, calculate its order ($N$), choose a high divisor as the subgroup order ($n$) and eventually find a suitable base point. That is: we won’t choose a base point and then calculate its order, but we’ll do the opposite: we will first choose an order that looks good enough and then we will hunt for a suitable base point. How do we do that?

Firstly, we need to introduce one more term. Lagrange’s theorem implies that the number $h = N / n$ is always an integer (because $n$ is a divisor of $N$). The number $h$ has a name: it’s the cofactor of the subgroup.

Now consider that for every point of an elliptic curve we have $NP = 0$. This happens because $N$ is a multiple of any candidate $n$. Using the definition of cofactor, we can write: $$n(hP) = 0$$

Now suppose that $n$ is a prime number (for reason that will be explained in the next post, we prefer prime orders). This equation, written in this form, is telling us that the point $G = hP$ generates a subgroup of order $n$ (except when $G = hP = 0$, in which case the subgroup has order 1).

In the light of this, we can outline the following algorithm:

- Calculate the order $N$ of the elliptic curve.

- Choose the order $n$ of the subgroup. For the algorithm to work, this number must be prime and must be a divisor of $N$.

- Compute the cofactor $h = N / n$.

- Choose a random point $P$ on the curve.

- Compute $G = hP$.

- If $G$ is 0, then go back to step 4. Otherwise we have found a generator of a subgroup with order $n$ and cofactor $h$.

Note that this algorithm only works if $n$ is a prime. If $n$ wasn’t a prime, then the order of $G$ could be one of the divisors of $n$.

Discrete logarithm

As we did when working with continuous elliptic curves, we are now going to discuss the question: if we know $P$ and $Q$, what is $k$ such that $Q = kP$?

This problem, which is known as the discrete logarithm problem for elliptic curves, is believed to be a “hard” problem, in that there is no known polynomial time algorithm that can run on a classical computer. There are, however, no mathematical proofs for this belief.

This problem is also analogous to the discrete logarithm problem used with other cryptosystems such as the Digital Signature Algorithm (DSA), the Diffie-Hellman key exchange (D-H) and the ElGamal algorithm — it’s not a coincidence that they have the same name. The difference is that, with those algorithms, we use modulo exponentiation instead of scalar multiplication. Their discrete logarithm problem can be stated as follows: if we know $a$ and $b$, what’s $k$ such that $b = a^k \bmod{p}$?

Both these problems are “discrete” because they involve finite sets (more precisely, cyclic subgroups). And they are “logarithms” because they are analogous to ordinary logarithms.

What makes ECC interesting is that, as of today, the discrete logarithm problem for elliptic curves seems to be “harder” if compared to other similar problems used in cryptography. This implies that we need fewer bits for the integer $k$ in order to achieve the same level of security as with other cryptosystems, as we will see in details in the fourth and last post of this series.

More next week!

Enough for today! I really hope you enjoyed this post. Leave a comment if you didn’t.

Next week’s post will be the third in this series and will be about ECC algorithms: key pair generation, ECDH and ECDSA. That will be one of the most interesting parts of this series. Don’t miss it!

Comments